Codices

These codices are without doubt the starting point for the most relevant research on Acolhua surveying. The two codices have been referred to as "sibling codices" because they come from the same place, were drawn around the same time and for the same purpose, they have identical format and type of information. They come from Tepetlaoztoc, a town located 6 km to the notheast of Texcoco in the State of México. The place has preserved its name as it appeasr in the codices and is still mostly rural. They were created around 1540 to aid in the lawsuit launched by the inhabitants of Tepetlaoztoc before the Real Audiencia de México against the spanish ruler (encomendero), Gonzalo de Salazar, for the excessive tributed he demanded from them. The documents of the "Salazar case" can be read, one part in the Archivo General de Indias en Sevilla, España (AGI, Justicia, Leg. 151 num. 1 y Leg. 159 num. 2) and another in the Archivo General de la Nación (AGN, Mercedes, vol.2, f109v-110r, exp.516) in Mexico City. The codices contain a census of each of the localities registered and its organization by household indicating the head of the household and its members. Then there is a section showing the landfields asigned to each household, with the lengths of the sides. The last section contains the corresponding areas of the fields. The codex Santa María Asunción registers census and fields for twelve localities in Tepetlaoztoc while the Vergara registers five. Even though the codices were drawn during the contact period, around 20 years after the conquest, the drawings, glyphs, numeric system, format and information registered are undoubtedly indegenous. These documents are probably copies of even older documents. The very content of the codices is worthy of attention because cadasters at that time in Spain did not contain sidelengths or areas (ref). One of the noteworthy contents of the codex is the use of square units of measurement. Since the unit of length was the tlalcuahuitl, "rod to measure land", which we will denote by T, the unit of measure for surfaces was the square tlalcuahuitl. Nowadays, after 150 of use of the metric system, this extension is natural but in the XVIth century it was not. The measures of land used then were caballerías, peonías, estancias de ganado menor, estancias de ganado mayor, etc. In fact the ambiguity in the definition of these quantities mean the conversion to the metric system is not well established. We are not aware of any record of the use of square units in other american cultures of the time. Unfortunately there is no evidence of its continued use in Tepetlaoztoc at later dates. It is a big loss for the cultural heritage of Mexico. HOW TO READ THE CODICES We now give a short explanation of each of the sections of the codices to facilitate their reading. CENSUS The census section, called tlacanyotl in Nahuatl consists of drawings of the faces of household member, with their christian name written in castillian in the upper part. Each head of the household is drwan at the left, usually next to a glyph for house (calli) and his/her name glyph to the left of the house.

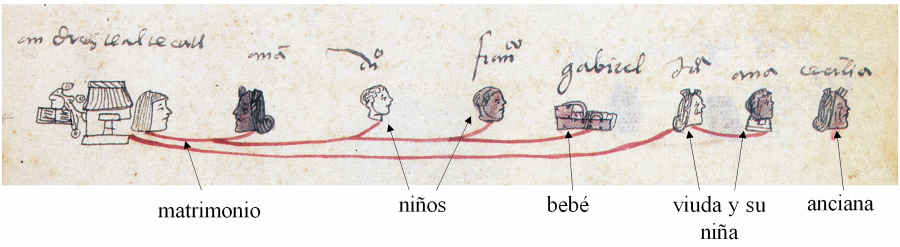

The faces distinguish the following categories:

Married man, married woman, unmarried man and woman, boy and girl, toddlers, widows and widowers, elderly man and woman.

The red lines that join the faces probably mean family relationship.

SIDELENGTHS

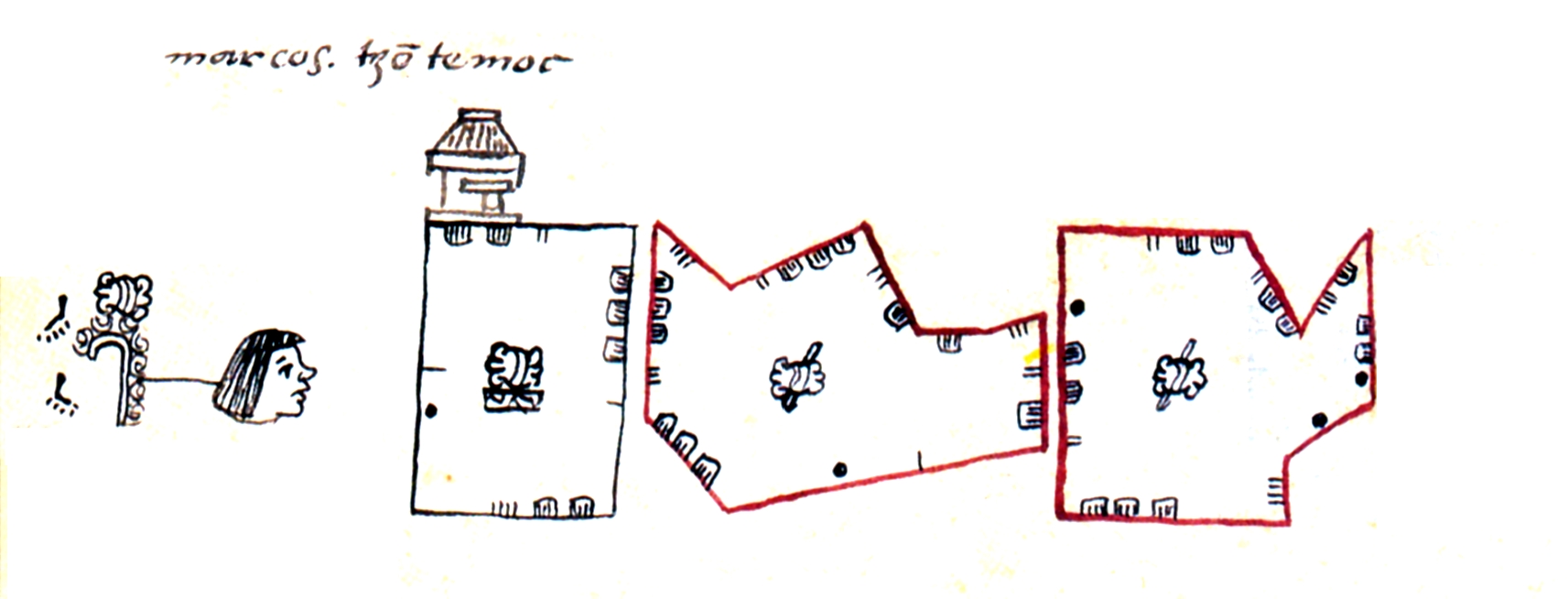

The second section of the codices is called in Nahuatl milcocoli, which means something with corners or curves and contains fields drawn and showing the sidelengths.

All of Mesoamerica used a vigesimal number system. The Acolhua culture used a line to symbolise one unit, five lines joined above by another to mean five units and a filled dot to mean twenty. There is no evidence of the use of zero among the acolhuas; nevertheless in the third section of the codices there is a kind of ad hoc positional system used to simplify the area records.

Apart from lines and dots there are three glyps: arrow, heart and hand. These glyphs represent fractional units that have been called monads to indicate they are independent of each other. The numbers on the sides of the fields are almost always written from left to right, from larger to smaller, with the monads at the end if required. Two monads never appear together.The use of fractions highlights another important characteristic of the acolhua, nemely their detailed recordkeeping.

It must be noted that the codices record with great care the number of sides of each field (there is one with 23 sides in Asunción) but the fields are NOT drawn to scale. For example in the rightmost field above, the bottom side measures 15T and looks larger that the side the measures 20T. Also the angles are not drawn correctly. We are not aware of any evidence of the use of trigonometry in the mesoamerican cultures.

AREAS

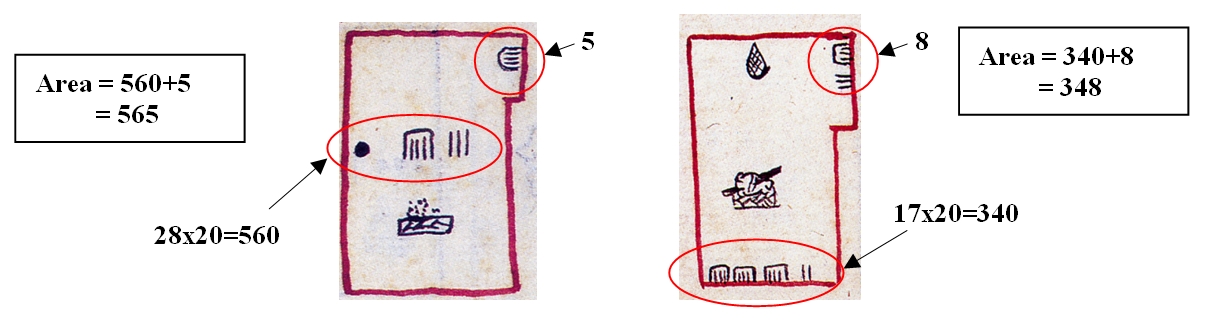

The third section is called tlahuelmatli in Nahuatl and means flattened, level; it consists of lists, as long as those in the milcocoli, of the fields belonging to each household with thier corresponding areas. The format used in this section is so different from the one used in the milcocoli that it was only deciphered in 1980. The cryptic system in this section is explained by the need to write very large numbers in a very compact way. Some fields have areas of thousands of square T.

Each register has a rectangular frame often with a tab in the upper right hand corner. There are only numbers in three locations: on the lower side, in the center and inside the tab. Numbers never appear in all three places at the same time. On the lower side numbers are never larger than 19 and in the center numbers are never smaller than 20. In the tab numbers are between 1 and 19.

The explanation of this ad hoc positional system is as follows.

The tab is where the units go. Since they use base 20, units go from 1 to 19.

If the area is larger than 400T2, to write it in the acolhua format it has to be decomposed into multiples of 20 and what remains are the units. The multiples of 20 are written in the center of the rectangle and the units in the tab. Numbers larger than 400 have at least 20 multiples of 20 so the number at the center is at least 20. For example:

Area = 565= 560 + 5 = 20 x 28 + 5

We write 28 at the center and 5 in the tab. The center is the place for the multiples of 20 so to read a number on the rectangle we multiply the central number by 20 and add the number in the tab.

If the area is smaller than 400, it is also decomposed into multiples of 20, what remains are the units, the units are written in the tab but the multiples of 20 are written on the bottom side. For example:

Area = 348= 340 + 8 = 20 x 17 + 8.

So we write 17 on the lower side and 8 in the tab. To read an area we multiply the number on the lower side by twenty and add the units in the tab.

There is another element that distinguishes fields with areas smaller than 400. It is a corn cob, cintli in Nahuatl, placed near the upper border. This glyph plays the role of zero to indicate that the field does not reach "one measure of land" which was 20 x 20 = 400 tlalcuahuitls 2. With this distinction it is easy to see at a glance which are the small fields. It may have been added to simplify the asignement if tributes.

If we see the limited space available to write areas and consider the fact that the acolhuas did not have a true positional system like the mayas, it is a very ingenious solution. This system of distinguishing between numbers larger and smaller than 400, writing digits in different parts of the rectangular frame and using a corn cob for fields smaller than one "medida de tierra" (unit of land) has been called by some authors an ad hoc positional system. LIGA

All the areas given in the tlahuelmatli are whole numbers, no monads appear. This does not mean that monads were not used during the calculations. There is evidence that they were used. It is only that the results were rounded to the nearest integer. LIGA

SOIL TYPES

Each field, both in the milcocoli and in the tlahuelmatli, has a glyph at the center. They have been identified as soil types; there are dozens of variants and combinations.

DATA BASES

We have created a database for each codex with the information on the fields belonging to each house, their sidelengths, areas and other relevant information. LINK SOON.

REFERENCES

Codex Santa María Asunción is kept at the Biblioteca Nacional de México, at the main campus of the National Autonomous University, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, classification: MsI497 bis.

Codex Vergara is in the Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris/Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicains, Ms. 37-39 and can be seen online here.

For a more in-depth explanation of the contents of the codices look at the publications with commentary:

Codex Santa María Asunción was published, with commentary, by the University of Utah:

“The Códice de Santa María Asunción. Facsimile and Commentary: Households Lands in Sixteenth-Century Tepetlaoztoc”, Barbara J. Williams and H. R. Harvey, University of Utah Press, 1997.

The spanish translation of the commentary is HERE. LIGA

PONER LIGA

Codex Vergara was published, with commentary, by the Instituto de Investigaciones en Matemáticas Aplicadas y en Sistemas of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México:

“El Códice Vergara. Edición facsimilar con comentario: pintura indígena de casas, campos y organización social de Tepetlaoztoc a mediados del siglo XVI”, Barbara J. Williams y Frederic Hicks, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México y Apoyo al Desarrollo de Archivos y y Bibliotecas, de México A. C., 2011.

Códice Asunción |

Códice Vergara |

|

|

|

Versión facsimilar del Códice Vergara |

|

|

|